Landcare is a community-based movement that began in Victoria in 1986, when Joan Kirner, (Minister for Conservation, Forests and Lands), and Heather Mitchell, (president of the Victorian Farmers Federation) joined forces to create Land Care.

It now involves thousands of Victorians in hundreds of groups working together to shape the future of our land, biodiversity and waterways. https://www.landcarevic.org.au/home/what-is-landcare/.

Landcare evolved as concerned land managers (mostly farmers) wanted to tackle dryland salinity, tree loss, soil erosion and many other pressing environmental issues. A group of farmers near St Arnaud, in central Victoria formed the first Landcare group. For these farmers, it made sense to work together to tackle their shared environmental problems.

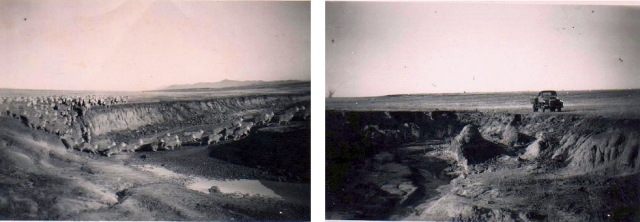

Gully erosion – Captain’s Creek

Gully erosion – Captain’s Creek

The movement has grown from this to the adoption of a broader focus on sustainable management of all of Victoria’s natural resource assets. It now encompasses individuals and groups across the whole landscape from coastal to urban and remote areas of Victoria.

The Landcare movement became truly national in 1989, when Rick Farley of the National Farmers Federation and Phillip Toyne of the Australian Conservation Foundation worked with the Hawke Labor Government to create the National Landcare Program.

Before Landcare started in Victoria, the state government tackled environmental issues with the Land Protection Incentive Schemes (LPIS) administered by the Department of Conservation, Forests and Lands and the Soil Conservation Authority (SCA). Many LPIS grants were for fencing and tree planting to reduce dryland salinity and erosion impacts. The SCA designed and constructed many concrete drop structures at gully heads to stop the extension of gully erosion which threatened not only private land but public assets such as water supply dams with excessive siltation. Contour farming was practised to control water flow to reduce water speed and therefore the possibility of erosion using the natural topography of the land. Land capability and farm planning was used to determine the layout and position of farm dams, irrigation areas, roads, fences, farm buildings and tree lines.

In 1984, The Ian Potter Foundation became involved in its first major rural project:

The Potter Farmland Plan. https://www.ianpotter.org.au/news/blog/potter-farmland-plan/. The Potter Farm scheme established demonstration farms using best environmental practice methods including farm planning, farm forestry, wind breaks and land class fencing.

Waterman’s farm

Waterman’s farm

The foundation established demonstration projects on 15 farms, all existing properties in Victoria’s Western District. The project aimed to show that, working with farmers and using readily available techniques, some of the main causes of land degradation could be addressed and rural land could be managed to gain maximum production, while still working within the bounds of sustainability.

The farms were mostly around Hamilton as there was much evidence of widespread land degradation in the form of excessive tree clearing, erosion and salinity common to much of Australia’s farmland. Several farmers in the region were already actively working within Farm Tree Groups and had some knowledge about some of the steps needing to be taken.

Captains Creek

Aerial photo showing Captains Creek half way through farm

Aerial photo showing Captains Creek half way through farm

A drop structure was installed on our Ararat property at the head of an erosion gully on Captains Creek circa 1955. This structure is one of a few in the district still doing its job. The erosion was caused by a combination of overgrazing, highly dispersive sodic b horizons soils, ploughing in lands to drain swampy areas in the 1930’s and rabbits. About two kilometres of gully was created with many active heads of erosion as well as side movement along the creek. This type of erosion was widespread especially in upper catchments with skeletal soils and steep slopes. Many land management issues became worse in the war when labour was limited and seasons poor.

The structure which was repaired about 10 years ago has stopped the actively eroding head from moving into our neighbours property.

When Christine and I returned to the family farm at Ararat in 1982 south east Australia was in a severe drought. Spring failed and most farms were overstocked and with insufficient hay to get through an unknown period of dry. Bare paddocks started to suffer soil loss culminating in dust storms hitting Melbourne in 1983 and the horrendous bush fires locally in the Otways.

When we recovered from feeding sheep and had successfully negotiated an overdraft with our bank we reviewed the situation. Like many other farmers we needed to farm more sustainably. We joined a farm management group facilitated by Mike Stephens (Farm 500) and our local landcare group (Upper Hopkins Land Management Group) when it started in the late 80’s. We undertook a whole farm planning exercise which was very valuable. We also joined the Victorian Farmers Federation (VFF) which auspiced landcare as well as promoting farming as a business. Later we were founding members of the Environmental Farmers Network (www.environmental farmersnetwork.net.au) an organisation promoting sustainable farming policies and biodiversity conservation on farms.

Farm 500 was an opportunity to share information and learn best practice from fellow farmers. It allowed us to think critically about our aims as family farmers and to understand the drivers of agriculture. Farming businesses have changed considerably over the years. Farm sizes keep increasing and enterprise mix is also changing. Most farms now have less stock and more crops as the climate dries and heats. Farming has become a higher risk business. Specialist Merino wool growing is now greatly diminished. Many sheep do not require shearing (eg Dorpers) and are grown for meat. High quality stock water is now at a premium as droughts are longer and evaporation rates higher. Rainfall patterns have changed, the annual amount reduced and winter/spring runoff to fill dams is less likely to occur. Reticulated stock water is now being rolled out for a large area south of Ararat. Increased cropping further reduces runoff to rivers.

Initial landcare activities had a heavy concentration on pest plants and animal control and, in our area, dryland salinity amelioration in the early days. Protecting waterways by fencing for stock exclusion and revegetation to build wildlife corridors was a later focus for most landcare groups. In the early days we needed to travel west of Horsham (Wail) to buy native trees (mostly non indigenous and from WA) or order from the Natural Resources Conservation League (NRCL) nursery in Springvale and have the trees delivered by rail! We also started to grow anything we could ourselves using four inch pots. I can remember digging up pine trees on roadsides and planting them in our front drive. These trees are still valued by the black cockies that visit occasionally.

Windbreaks for sheep off shears were an early priority on the basalt plains. Biodiversity improvements were a bonus but not a driver for tree planting.

We spent weeks spraying gorse on Captains Creek at the downstream end and began fencing and planting native trees at the upstream end where weeds were not a problem but rabbits and erosion were. We were hoping that one day habitat values would be good enough to attract White-winged Choughs that were once present at a nearby property until they were shot much to the horror of ourselves and our old farming neighbour who was quite proud of them.

After many years of consistent landcare work the entire length of Captains Creek on our block (3km) is now double fenced and planted with a variety of mostly indigenous plants. The variety of bird life on the farm has increased and White-winged Choughs have found the creek to their liking after visiting a year or so ago. They bred successfully in spring 2019. We also have resident White-browed Babblers appreciating the hedge wattle as safe nesting and resting places.

Over the years we have gone from planting narrow strips with foreign trees to wider and wider strips with indigenous plants. Planting is now wider spaced as plants compete in dry years causing deaths or stunted growth. Land class fencing for slope, soil types and land capability are now considered normal and planting woodlots on a paddock scale are encouraged in appropriate places to recreate Ecological Vegetation Classes (EVC’s). Many farmers have co-operated to link plantings especially along waterways to create biolinks. Preserving native grasslands, wetlands and grassy woodlands are a high priority.

These days landcare is involving farmers in sustainability issues such as reducing chemical reliance, integrated pest management systems, soil health, reduced reliance on artificial fertilisers and planning for fire events. Many Ararat Hills farmers now host wind farms which are financially rewarding and a constant reminder of renewable energy solutions to combat climate change impacts.

Gorse, rabbits and foxes are still issues on many farms and require constant monitoring and an annual work program. Work to control gorse on farms has been assisted with the formation of an urban landcare group at Ararat in the upper catchment. Both the urban and rural groups are active today. The Victorian Gorse Task Force supports community-led gorse control projects and administers grants to groups of private land managers to control gorse. It provides associated educational material to assist the public on its website – https://www.vicgorsetaskforce.com.au/

The Upper Hopkins Land Management Group https://upperhopkins.org.au/ which started on the plains south of Ararat eventually expanded its area to take in all of the upper farming catchment. This was logical as the land practices in the hills were affecting the farms on the plains. Tree clearing on the hills caused dryland salinity on lower slopes and plains. Gully erosion was silting up the deep holes that platypus and other aquatic life rely on in the Hopkins River.

While farming is a constant battle against many unknown events including short and long term climate impacts and local and international market forces, it can still be a highly rewarding occupation especially when you see real environmental improvements in your life time both on your own patch and the local catchment.

Peter and Christine Forster